*Thank you to membership contributions for this article. It has been published in its entirety without any edits from MMEA Executive Director, Jerri Neddermeyer. If any membership wishes to contribute an article during our time without an editor on the board, please submit articles to execdirector@mmea.org. All submissions will be evaluated based solely on available time to manage administratively, and with considerations toward avoiding conflicts of interest and self-promotion. (Jerri D. G. Neddermeyer)*

Music Teacher Burnout and Work-life Balance: Perspectives from Minnesota

David Edmund

Dylan Reed-Fuglestad

Imagine: It’s late spring on a beautiful Friday afternoon and you have evening plans with a spouse, friends, or family. After another long week of prepping, teaching, attending meetings, communicating with parents, and working with administrators, you head home anticipating the fun evening out. Perhaps it’s an upscale meal, or a trip to the community theater to see the latest production. Upon arriving at home, you take a moment to sit down and relax, realizing that it’s the first moment of the day (other than your 30-minute lunch “break”) that you actually gave your feet a rest. After a few minutes, you close your eyes, reflecting upon the teaching challenges and successes of the week. And then . . . you’re out. The power nap is necessary; it’s useful, but also a reminder that you only have so much energy left. In lieu of the exciting plans you had, you opt for a quiet dinner at home and an early retirement for the night.

If you are a music educator, you probably relate to this scenario. You’ve likely sacrificed countless family and social events due to exhaustion. You’ve likely dealt with work-related stress, sleep deprivation, and some degree of anxiety. Is this the life of the music educator that you envisioned during teacher preparation and upon entering the profession? Of course not. You prepared for and entered the profession with dreams of sharing music with young people, expressing yourself musically and pedagogically, and celebrating the great successes of your students. Work and life, though, seldom seem to actually be in balance, sometimes leading to burnout.

Scholars (Bernhard, 2016; Robinson, 2020) note that music educators, perhaps more than most professionals, deal with work-related stress, struggle with work-life balance, and deal with burnout. Across disciplines, today’s teachers are facing burnout at increasing levels and it is contributing to the existing teacher shortage throughout the United States (Matthews & Koner, 2017; Walker, 2022).

Music Teacher Burnout

In 2021 the Minnesota Professional Educator Licensing and Standards Board (PELSB) published a report related to teacher supply and demand. The report’s findings included the following:

- 70% of school districts reported being somewhat significantly or very significantly impacted by the teacher shortage.

- 88% of school districts reported being somewhat significantly or very significantly impacted by the substitute teacher shortage (PELSB, 2021).

Teacher shortage is a problem in other states too, and the effects of teacher burnout cannot be dismissed. In particular, music teacher burnout appears to be a problem, with work-life balance (or imbalance) being a factor. Robinson (2020) examined work-life imbalance among secondary school music teachers, finding that first year teachers struggled with long hours and questioned whether such a work schedule was sustainable. Resilience and the establishment of work-life boundaries were primary factors among those who lasted in the profession.

Issues with burnout and work-life imbalance, however, are not exclusive to early career teachers. Ballantyne & Retell (2020) obtained data from veteran teachers who dealt with burnout, citing factors such as challenging student behaviors, administrative pressure, and career stagnancy. Jerrim and Sims (2021) found that excessive workload contributed to increased stress, compromised wellbeing, and teacher attrition. It was further determined that 55 hours per week constituted a threshold that once crossed, became a magnifier for the impact of stress. Crossing the 55 hour threshold was found to have a distinct negative impact upon quality of life (Jerrim & Sims, 2021).

Bernhard (2016) suggested that music teachers in their early career years and those who taught multiple age levels consistently experienced higher levels of burnout than their peers who taught in other disciplines. According to Garrick et al. (2018), “Time spent (at home) in work-related activity was significantly related to higher levels of fatigue, indicating that the high levels of non-paid work that teachers are required to complete outside of work hours is detrimental to staff wellbeing” (p.248).

Impacts of Work/life (im)balance and Music Teacher Burnout

To further investigate the problem, we surveyed Minnesota band directors (n = 31) to examine their perceptions about the impact of work-life balance upon teacher burnout. Our study was approved by the University of Minnesota’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). While not surprising, the findings were compelling.

A twenty-item survey was distributed, which addressed:

- Hours devoted to work outside of the contracted hours

- Participants’ satisfaction with work-life balance

- Participants’ experiences with teacher burnout

- Participants’ overall job satisfaction and intent to remain in the profession

A near equal balance was gathered between female (n = 15) and male participants (n = 16). Longevity in the profession was also well-balanced among participants. While only six participants had taught five years or less, nineteen participants had 10 or more years of teaching experience (average years teaching = 10.7). The following are some of the key findings.

Of the Minnesota band directors surveyed, only 19% indicated that their current work-life balance was sustainable. 94% of the participants reported experiencing feelings of burnout, and 77% of participants considered leaving the teaching profession due to burnout.

- Participants reported working an average of 9.5 hours per week outside of contracted hours. Many reported working 20 or more hours per week outside of their contracted hours.

- 24 participants reported some level of agreement with the statement that they were frequently the first educator to arrive on campus in the morning, or the last to leave after the work day (9 participants selected “strongly agree.”).

- Only 3 participants reported some level of agreement with the statement that eight hours per day is an adequate amount of time to complete job tasks. Notably, those three individuals also reported working an average of 0-5 hours per week outside of their contracted hours.

- 15 individuals strongly disagreed that eight hours per day was sufficient (Table 1).

These results suggested a workload problem for Minnesota band directors. While music educators are not exclusively over-worked when compared with teachers in other disciplines, the teaching of music often calls for duties that must be performed on campus (i.e. practicing instruments that are housed on campus, repairing equipment, and maintaining the library of musical scores). The luxury of working from home appears to be less available to music educators.

While survey responses related to work-life balance revealed greater variation, participants felt that their work-life balance was generally worse than that of their colleagues who taught in other disciplines (Table 1).

- 18 participants reported lacking a satisfactory work-life balance. Six participants were neutral on the item and seven reported some level of satisfaction.

- In comparison with the work-life balance of teachers in other subjects, 23 band directors reported to some extent that theirs was worse.

Table 1

Perception of Work-Life Balance and Working Hours

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Neutral | Somewhat Agree | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| I am satisfied with my current work-life balance | 5 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| As a band director, I feel that I have better work-life balance than teachers in other content areas

I am frequently either the first educator to arrive in the morning and/or the last educator to leave at the end of the work day

Eight hours a day is an adequate amount of time for me to do my job satisfactorily. |

10

1

15 |

12

4

10 |

1

1

3 |

4

2

0 |

4

9

1 |

0

5

1 |

0

9

1

|

Respondents also acknowledged not having enough time to pursue enjoyment outside of work. Twenty-one respondents felt that their family life had been compromised due to a lack of work-life balance (Table 2).

Table 2

Life Outside of Work

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Neutral | Somewhat Agree | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| I have enough time to pursue the things I enjoy outside of work. | 7 | 7 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 7 | 0 |

| My family life has been compromised by my current work-life balance | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 11 | 6 | 4 |

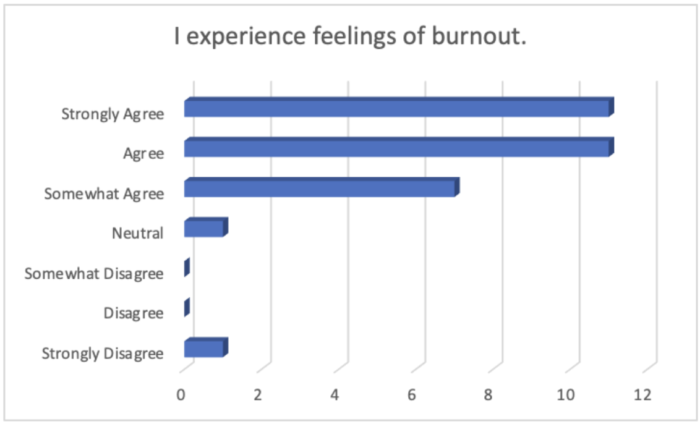

Data analyses suggested links between items related to work-life balance and teacher burnout. Statistical results from those analyses were beyond the scope of this paper, but the following data points provided further evidence regarding teacher burnout for band directors in Minnesota. To begin, 29 participants (94%) reported some level of burnout (Figure 1). While causation may be another matter and likely involves several factors (low pay, lack of support, lack of respect, etc), survey results clearly suggested a relationship between burnout and issues with work-life balance. If the relationship exists, improving teachers’ work-life balance may result in a reduction of burnout.

Figure 1

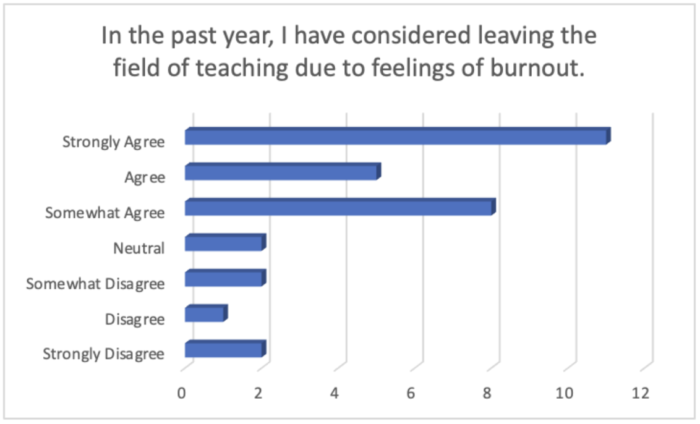

Perhaps the most troubling findings from the study were that a) the current lack of work-life balance was not deemed sustainable, b) a strong relationship existed between perceptions regarding work-life balance and music teacher burnout, and c) participants expressed prominent thoughts about leaving the teaching profession (Figure 2). While Covid has had a negative impact upon teacher retention resulting in teacher shortages, music teachers were likely already experiencing struggles.

Figure 2

At the end of the survey, participants were asked to provide additional narrative related to teacher burnout and work-life balance. Analyses of the responses led to three themes: Strategies for improving work-life balance, the importance of family time, and the importance of prep time while on the job. Teachers who did not have children questioned whether or not they could do their jobs while raising a family. For those with children, work demands resulted in too many hours away from family members.

Participants also raised concerns about a lack of prep time, causing them to work extra hours during evenings and devoting a great deal of summer “vacation” time to planning for the upcoming school year. The lack of prep time also caused a reduction in time spent with spouses. Some teachers reported working late after their children and spouses went to bed. Some teachers indicated that prep times were increasingly devoted to subbing. While this particular symptom may be relieved with a reduction in Covid-related teacher absences, concerns about prep time will likely persist. Seldom do educators have duties lifted from their load; in fact, it’s quite the opposite. Expectations for measuring student achievement continue to rise and the library of curricular materials continues to expand, causing teachers to invest more time toward reviewing materials, and finally licensing requirements continue to expand.

Recommendations

Results from our study suggested distinct issues regarding work-life balance, teacher burnout, and teacher retention for band directors in the state of Minnesota. We must note that these results were obtained from a limited sample of participants, but based upon extensive literature, similar problems exist throughout the teaching profession. Given the extent of the results reported by band directors, concerns regarding work-life balance and teacher burnout likely relate to other music educators as well.

So what can we do about these issues? One of our purposes for this article is to increase awareness related to work-life balance and teacher burnout for all music educators. With that purpose in mind, we provide the following suggestions for dealing with work-life imbalance and teacher burnout. The suggestions are not all-encompassing, but may constitute a good starting point for assisting music educators to overcome said challenges. Given what may be referred to as a crisis for teacher retention, self care and wellness are vital. We hope that one or more of the following suggestions will help.

- Make use of online professional development resources, such as the Musician’s Way. This site contains countless articles, web links, and videos that address everything from practice tips to creativity and wellness for musicians.

- Engage with mindfulness for musicians. A quick online search for “mindfulness for musicians” will uncover a number of websites and documents for improving concentration and relaxation, while reducing stress.

- Take advantage of resources from the various music education professional organizations, including NAfME. In addition to a recent series on self care for music educators, NAfME hosts numerous articles pertaining to teacher burnout.

- Network with other teachers through social media. Participating in an online community offers opportunities for support and guidance. It also contributes to one’s sense of community. Simply knowing that you are not alone can be a great benefit.

- Maintain your physical and emotional health. This might involve exercise, diet, yoga, meditation, or other interventions. Improved physical wellness contributes to improved emotional health, overall wellbeing, and job performance.

- Monitor and manage the amount of additional time spent on the job. Remember the 55 hours threshold cited by Jerrim & Sims (2021)? The threshold will be different according to each individual, but establishing and maintaining your limits will contribute to a healthier and happier working life.

- Read a book for personal and or professional enrichment. We recommend something that stimulates your imagination and offers a departure from everyday life. Ask colleagues what they enjoy reading and if given the opportunity, engage in healthy discussion about the things you are reading. Reading groups can engage informally over coffee or during happy hour.

- Seek opportunities for mentorship. While mentorship was not a primary focus of this article, there is a substantial body of literature on the benefits of mentorship for professional educators. This applies to all music teachers, regardless of experience. Having an additional pair of eyes and ears can be very beneficial for professional development, both intellectually and emotionally.

- Last, but certainly not least, remain active as a performing artist. Sing or play in a community ensemble, at a place of worship, or in a garage band. So much of our personal identity results from active music-making. If we would seek lifelong participation in music-making for our students, we should seek it for ourselves.

Further research is needed to address work-life balance and burnout among music teachers. Such examinations should address music teachers who work with different age/grade levels and those who teach in different states. Researchers will need to consider the effects of the pandemic, including its impact upon teacher retention. Causes and effects of work-life balance should be examined carefully, including experimental intervention-based studies.

We recognize that work-life balance is not the only contributing factor to teacher burnout. However, it is a contributing factor and one which teachers have some control over. Teachers may not have much control over salary or other contributing factors, but we can establish healthy boundaries between work, recreation, rest, and other sources of enjoyment.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Ballantyne, J., & Retell, J. (2020). Teaching careers: Exploring links between well-being, burnout, self-efficacy and praxis shock. Frontiers in Psychology, 10 (pp.1-13).

Bernhard, H. C. (2016). Investigating burnout among elementary and secondary school music educators: A replication. Contributions to Music Education, 41 (pp.145-156).

Garrick, A., Mak, A. S., Cathcart, S., Winwood, P. C., Bakker, A. B., & Lushington, K. (2018). Non-work time activities predicting teachers’ work-related fatigue and engagement: An effort-recovery approach. Australian Psychologist, 53 (pp.243-252).

Jerrim, J., & Sims, S. (2021). When is high workload bad for teacher wellbeing? Accounting for the non-linear contribution of specific teaching tasks. Teaching and Teacher Education, 105 (pp.1-10).

Matthews, W., & Koner, K. (2017). A survey of elementary and secondary music educators’ professional background, teaching responsibilities and job satisfaction in the United States. Research & Issues in Music Education, 13(1) (pp.1-25).

PELSB (2021). 2021 Biennial Minnesota teacher supply & demand. St. Paul MN (pp.1-52). Retrieved March 16th, 2022 from http://tinyurl.com/4hmjcy7d

Robinson, J. (2020). A national snapshot of early-career secondary school music teachers: Engagement, obstacles and support. Australian Journal of Music Education, 53(2) (pp.50-56).

Walker, T. (2022, April 14). Beyond burnout: What must be done to tackle the educator shortage. neaToday. http://tinyurl.com/ymvmub7z

0 Comments